News Alert: New ePCR Integration Simplifies EMS Data Management and Enables Better Care Coordination

COVID-19 Workforce Impacts and Data Collection: A Study in Collaboration

(8 min read) In early 2020, the concept of the novel coronavirus was nothing more than a whisper in New Jersey EMS agencies

Was this information valuable?

(8 min read) In early 2020, the concept of the novel coronavirus was nothing more than a whisper in New Jersey EMS agencies. It was mentioned on daily briefing calls but was not considered a life-changing event. As the virus took hold and its impact became a very serious concern to the Advanced Life Support (ALS) Units in the state, agencies in the New Jersey Association of Paramedic Programs (NJAPP), turned to each other for guidance, and to share best practices, data, and support.

Once in a Lifetime

Starting in late March, the state of New Jersey found its citizens and healthcare workers in a life-changing struggle. Over the span of several weeks, EMS agencies went from seeing COVID-19 unfold on the news to living it on a daily basis and expending all of our collective efforts on how to respond to an incredible surge in call volume, patient acuity, and provider risk in the face of rapidly evolving and often conflicting guidance.

NJAPP, a nonprofit advocacy group comprised of the 20 hospital-based ALS providers in New Jersey, quickly began efforts to share information and best practices for responding to this unprecedented threat. Some of the data we began to collect, to the best of our ability, related to workforce impacts, specifically providers who were ill or presumptively positive, those who were hospitalized or ultimately died from COVID-19, and those who were unable to work in our system because of other job restrictions.

New Jersey has a unique EMS system, with 100% ALS coverage by hospitals, all of whom are granted a primary response area through the Certificate of Need process, and with BLS provided locally by varying departments. Our member hospitals provide a spectrum of EMS services, including 911 and non-emergency BLS, communications, specialty care ground transport, air medical transport, and more. There are numerous ways in which this system structure will limit the applicability of our data to other systems, including the uniform foundation in the healthcare system and the fact that virtually all of our providers work multiple jobs — both in EMS and in other public safety systems. Regardless, it is our goal to share our lessons with the community in the hopes that others can learn from our experiences.

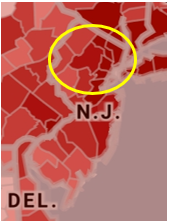

New Jersey: a Tale of Three Regions

These observations and lessons learned come from the combined experience of 11 New Jersey hospital-based EMS agencies. Because the scope and impact of pandemic response varied from county to county, with the hardest hit counties in the northeast of the state, it makes the most sense to frame the discussion in terms of three separate regions. Although we’ll discuss each of the three regions individually, it is important to note that some of the reporting agencies straddle more than one region, and many of the reporting agencies share providers that work and live in more than one region.

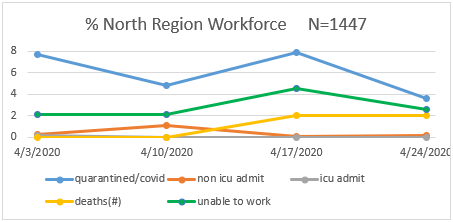

Northern Region: Ground Zero

Northern New Jersey was hit first and hardest in late March and early April and served as the bellwether for other regions as the pandemic spread and picked up speed. On hotspot maps depicting COVID-19 infection, this region was shaded in the darkest color, indicating the hottest of hotspots.

This region saw a significant impact on the EMS workforce. Six agencies combined to report data for this region, totaling 1,447 basic and advanced life support providers, field nurses, and communications personnel. Between 3.5 and 8% of providers either tested positive or displayed symptoms that classified them as presumptive positive cases requiring quarantine throughout the duration of April. Additionally, this region accounted for the only significant numbers of ICU admission and death among EMS providers among the agencies submitting data. An additional 2 to 5% of the workforce was limited by their primary employer to only work a single full-time position, resulting in less per diem availability and support across the region. At the height of the pandemic response, between 12 and 15% of the EMS providers in this region were unable to report to work due to the confluence of these factors. This does not include a rapid decline of volunteerism in the region during the same timeframe, further compounding response issues and leading to an urgent need for additional units and FEMA support.

Many of the lessons learned through trial and error in the northern region saved time, resources, and lives throughout the rest of the state. It quickly became evident that in order to support increasing 911 volume, additional units would be needed in the affected area, existing units would need to utilize creative staffing models, and dispatch centers would need to be more willing to tap non-traditional mutual aid resources.

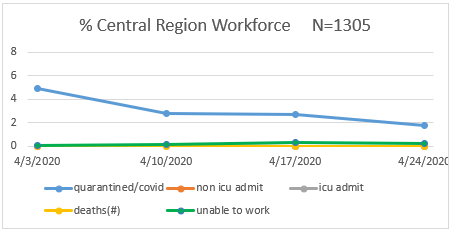

Central Region: A Mixed Bag

Although many areas of central New Jersey lack the population density of those counties located closer to New York, some of the state’s largest cities exist in this region, as well. For this reason, analysis of the Central Region is truly a mixed bag, with local hotspots giving way to more dispersed populations with fewer cases. In terms of visual representation, counties in this region were depicted by one of the three darkest/hottest colors, with some counties hit with the same intensity as those in the northern region.

Two large agencies combined to report data for the central region, totaling 1,305 basic and advanced life support providers, field nurses, and communications personnel. Between 1.5 and 5% of providers either tested positive or displayed symptoms that classified them as presumptive positive cases requiring quarantine throughout the duration of April. No ICU admissions or deaths were reported between the two EMS agencies submitting the data reflected here, although ICU admits and deaths among other EMS providers were reported in this region during this timeframe. An additional 1 to 2% of the workforce was limited by primary employer to only work a single full-time position, resulting in less per diem availability and support across the region. At the height of the pandemic response, between 3 and 6% of the EMS providers in this region were unable to report to work due to the confluence of these factors. The central region fared better than the northern region, but still relied on additional resources and FEMA support during the peak period.

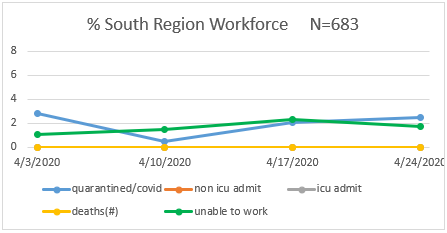

Southern Region: The Land of Cautious Optimism

New Jersey’s southern region fared relatively well in April, all things considered. On heat maps, the region was characterized by lighter shades, with localized hotspots closer to the Philadelphia metro area. Three EMS agencies combined to report data for this region, totaling 683 basic and advanced life support providers, field nurses, and communications personnel. Between 0.5 and 3% of providers either tested positive for COVID-19 or displayed symptoms that classified them as presumptive positive cases requiring quarantine throughout the duration of April. No ICU admissions or deaths were reported among the EMS agencies submitting data reflected here; however, an additional 1 to 2.5% of the workforce was limited by primary employer to only work a single full-time position, resulting in less per diem availability and support across the region. At the height of the pandemic response, only 0.5 to 5% of the EMS providers in this region were unable to report to work due to the confluence of these factors.

Key Takeaways for EMS Agencies

In light of this data, NJAPP can share a number of COVID-19 response recommendations to EMS agencies. First, get ahead of the curve on the situation, especially regarding data collection about your workforce and with distribution of data to your personnel and any oversight bodies. In New Jersey, we found it challenging to begin the data collection process while everyone was deep into pandemic response, and that hampered our efforts. Make sure you have good data definitions, share them widely, and collect the data centrally.

At the same time, be wary of data overload. Today, we are more than four months into the pandemic, and while the gravity of the situation is still in flux and varies greatly by geography, we now have a better handle on best practices for medicine, operations, decontamination, provider mental health, and more. Back in April, New Jersey EMS personnel were overloaded with daily changes as we attempted to keep up with the disease and current response protocols. Data distribution was challenging during this chaotic time. The best advice is to be aware that your personnel and oversight groups will be drowning in information and providing them with manageable systems to process data and discern the “signal” from the “noise” will be critical. Emphasis on quality data to support decisions is even more important, considering the alternative information sources, including but not limited to social media, that may be publishing erroneous or outdated information.

While it seems obvious, our ability to work together in New Jersey was of paramount importance in navigating this crisis. New Jersey has a very limited breadth of ALS providers, which gives us a manageable span of control. At the same time, we often find ourselves in competition with each other and are, therefore, reluctant to share data. During the height of the pandemic here, all providers put these concerns aside and shared information without hesitation. The free flow of information was even more critical, because our hospitals are the safety net for the community-based BLS agencies in New Jersey. As BLS resources became compromised due to reduced workforce, increased volume, and ceased operations, our hospitals scrambled to fill in those gaps.

Finally, while we now have a much better handle on workforce protection and are not experiencing as many problems related to providers who are exposed to COVID-19 and presumptive or actually sick, there will be persistent challenges associated with our per-diem personnel. Many of them work full-time as police officers, firefighters, dispatchers, and nurses, and those employers restrict employees’ ability to work in the EMS environment in order to protect their own systems. Depending on your system design and staffing model, the restricted availability of per diem personnel could place significant strain your workforce. If you end up with a large number of providers out sick with COVID-19, you may discover that you don’t have the “bench” that you normally would expect to have.

Our experiences in New Jersey will be different in many ways from your own. We got hit with the pandemic early. Guidance was confusing and contradictory. The severity of the virus was not truly realized until the impact on cardiac arrest patients hit home. In some cases, cardiac arrest patients were held with no units to send, while other patients held SpO2 rates of 60% and conversed coherently until they just collapsed in cardiac arrest in front of medics. At its worst, the pandemic was nothing short of a daily multiple casualty incident (MCI). Our ability to handle the volume and to somehow maintain the morale of our staff — who feared for not only their lives, but for the lives of their loved ones — was a leadership challenge that exceeded anything we had experienced before. Let’s hope that the learnings from our region can help agencies in other locations to be better prepared earlier for a surge, if and when one descends upon their state.

Read more about strategic applications for ePCR data:

Related Posts

4 Must-have Data Points for Dispatch-Billing Alignment and Maximum Reimbursement

How STAT MedEvac Connected Device, Software, and Data Technology To Enhance QA and Elevate Care

ZOLL Pulse Blog

Subscribe to our blog and receive quality content that makes your job as an EMS & fire, hospital, or AR professional easier.

ZOLL Pulse Blog

Subscribe to our blog and receive quality content that makes your job as an EMS, fire, hospital, or AR professional easier.